Greetings from the AiRMOUR External Advisory Board: Director Judith O’Meara, EIT Urban Mobility, Innovation Hub Central

‘The European Green Deal, the EU’s new growth strategy, calls for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions as well as the development of digitalisation. The transport system as a whole should be made smart and sustainable, with the uptake of innovative technologies such as electrically and hydrogen-powered aircraft.

From the point of view of EIT Urban Mobility — an initiative of the European Institute of Innovation & Technology (EIT), a body of the European Union — a holistic future-forward vision is essential for implementing UAM and drone services in Europe while taking aspects such as safety, security, societal acceptance, and sustainable development into account. In this context, improved collaboration between private and public entities is the key.

In the light of the European Green Deal, and Smart and Sustainable Mobility Strategy, the main areas to be focused on in the development of Urban Air Mobility are 1) Ensuring a harmonised legal and technical certainty on the EU level, to support research and infrastructure initiatives, and to encourage private sector investments. 2) Mapping living labs, to take stock of the progress made in implementing UAM, and to identify citizens’ and stakeholders’ needs that can be efficiently addressed by UAM.

In addition to the climate change challenges, rapid urban growth raises the need for developing and implementing strategies to promote alternative sustainable mobility solutions. The future of urban mobility could be played up in the air. Air Emergency Medical Service (Air EMS) provides unique and important opportunities in the field of medical transport.

Medical professionals, emergency responders, and hospital staff face a host of challenges on a daily basis, challenges UAM can help overcome. Drones make it possible to deliver blood, vaccines, and other medical supplies to rural areas and have the ability to reach victims who require immediate medical attention within minutes. New operational models that leverage UAM markets show promise to enhance Air EMS scale, and emerging technologies such as flight automation and electric aircraft show potential in increasing Air EMS safety and provide opportunities to deploy Air EMS assets as part of a UAM system to increase utilisation.

Zipline has established a feasible business model to streamline global health supply chains since 2016. In 2020, the COVID-19 lockdown caused health threats to outpatients at the Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence, Rwanda’s main cancer care referral centre, managed by the Rwandan government and Partners In Health. To this end, Partners In Health collaborated with Zipline to deliver cancer medications to local district hospitals. On-demand delivery reduced average patient travel time by 85%, reducing the risk of exposure, and increasing access to critical medicines and health care [1].

As drones are incorporated more into the health care sector, delivery and courier services provide the most potential benefits. More research is therefore required in order to further identify impacts on a city and regional level and to form guiding principles and measures in municipalities’ city planning efforts. The EU-funded AiRMOUR project focuses on identifying novel concepts and exploring solutions supporting sustainable air mobility in urban contexts via emergency and medical services. Through research and additional live validations in three European countries: Norway, Finland and Germany, and simulations in Luxembourg, the project will generate knowledge in the form of a guidebook for cities, operators and other stakeholders, a GIS Tool for urban planners, and a training programme. The identified best practices and project use cases can guide other European cities in integrating Air EMS into their urban planning processes, and support decision-makers in implementing strategies encouraging a more sustainable and integrated transport system.’

On the role of EIT Urban Mobility in UAM:

‘An increasing number of calls for R&I projects and city pilots on UAM are being launched and implemented in Europe with the goal to create an environment where solutions can be tested, and where experiences are continuously exchanged. It is the key to ensure that the resources in place are being managed and used properly, taking advantage of a range of synergies resulting from cross-field activities and multi-stakeholder cooperation.

In 2021, EIT Urban Mobility initiated the Special Interest Groups (SIGs), to shape the future mobility landscape by fostering public-private collaboration, addressing key urban mobility trends. The ambition of EIT Urban Mobility’s Special Interest Group on Urban Air Mobility (UAM-SIG) is to support all UAM actors in the complex process of mobility transition we are facing, to create an ecosystem and to facilitate its development, in which all views and experiences are included.

With this initiative, we have run several sessions with city authorities and key players, to identify best practices and relevant use cases that can address challenges faced by European cities, and to give feedback and recommendation for our upcoming Thought Leadership Study on UAM.

The UAM Plazza Accelerator Programme helps early-stage startups to scale up their business and provides them with the opportunity to implement their solutions in European cities. With our collaborative approach, we support responsible investments in technology, aligned with cities’ goals and offering solutions to urban mobility challenges.’

[1] Source: Zipline Capabilities Statement

Images: EIT Urban Mobility

‘It is essential to learn from the past when developing urban air mobility. Between 1953 and 1979, New York Airways operated a helicopter shuttle service between New York Cities Airports and Manhattan. The service was discontinued due to safety concerns following several accidents that resulted in personal injury. [1]. A similar UAM concept also existed in Los Angeles during this time. These were the first UAM applications.

Public acceptance levels declined rapidly after these accidents. The service was no longer in sufficient demand and had to be discontinued.

The success of UAM is mainly dependent on technical and organizational safety. UAM concepts must be safe so that passengers can use the service with a good feeling. It must also be ensured that the ground infrastructure enables safe flight operations.

EASA has published the first technical specifications for take-off and landing areas of vertiports for manned eVTOLs (electrical vertical take-off and landing). UAM services are likely to be provided mainly by eVTOLs in the future. The ground infrastructure required is therefore different from that of a conventional heliport, especially with regard to firefighting and passenger rescue. EASA refers in the technical specifications for vertiports to emergency procedures for conventional heliports. These precautions and methods must be adapted. Suitable fire extinguishing devices must be available to effectively fight fires of lithium-polymer or lithium-ion accumulators.

Passenger rescue from an electrically powered aircraft is also different from passenger rescue from an aircraft powered by conventional fuels. Emergency services must be properly trained and equipped. Who is responsible in the event of an emergency, the municipal fire department or the airport fire department? These and similar questions must be clarified. Adequate emergency standards must be in place before personnel-carrying UAM concepts can be implemented.

The operation of Unmanned Aircrafts (UAs) as a component of UAM or AAM (Advanced Air Mobility) could gain new momentum in 2023.

With the possibility of establishing U-Space airspaces in the European Union member states starting in 2023, Unmanned Aircrafts could become an even more significant part of the value chain. In theory, U-Space airspaces enable automated beyond visual line-of-sight (BVLOS) operations. UAs could thus open up regular and terminable transport capacity for useful applications such as transporting medical products, lab samples, important documents, etc. The transport of fast food, internet store products, etc. is explicitly not included.

However, setting up U-Space airspaces alone is not enough. The potential can only be exploited if the responsible authorities in the individual EU member states can also approve automated BVLOS operations. In Germany, for example, only a few BVLOS projects have been approved so far. The reasons are mainly due to the very extensive and complicated approval procedures. The approval procedures must be optimized so that approvals can be granted more quickly, effectively and, above all, more easily.

Furthermore, appropriate U-Space service providers must be available to offer U-Space services at reasonable cost.

U-Space-Airspace means that UAs can be fully integrated into air traffic. It should not be forgotten that the airspace is not only used by commercial air traffic and private motorized air traffic, but also by sports aviation. Sport aviation includes non-powered privately used aircraft such as gliders, hang gliders, etc. Many sport pilots operate in airspaces where transponders are not mandatory. Consequently, the majority of these aircraft are not equipped with a transponder. For this reason, it should be ensured that the U-Space airspace areas are only as large as absolutely necessary, so as not to hinder the sport pilots in the pursuit of their hobby.’

[1] Garrow, L.A.; German, B.; Leonard, E. Urban Air Mobility: ‘A comprehensive review and comparative analysis with autonomous and electric ground transportation for incoming future research’; Transportation Research Part C (2021).

‘There are several immediate challenges for urban air mobility and drone services in Japan. Firstly, the legal issues: drone use by end-users is in the process of being regulated, while legislation for commercial use of drones is in progress. Specifically, an aircraft category for Level 4 flight and a drone pilot class will be established by the end of 2022. However, there have been few Level 4 demonstrations of large drones weighing more than 25 kg, and they are still in the realm of social experiments. In addition, large drones weighing more than 100 kg (150 kg in the future) are treated as unmanned aircraft under the civil aeronautics law and cannot currently fly without ensuring safety equivalent to that of an aircraft, creating a barrier to entry for drone manufacturers and start-ups.

Secondly, there are the manufacturing issues. In Japan, there is a movement toward fully domestic production of drones. While there are a certain number of manufacturers of large drone airframes, many of the major components such as batteries, motors, and flight controllers are made overseas. It is necessary to domestically produce key drone components while taking advantage of Japan’s strengths in cameras, sensors, wireless piloting, carbon products and so on. Japan has few manufacturers of large eVTOL airframes like those used for urban air mobility, and only a few companies produce single-seat eVTOLs. Several startups have emerged that aim to manufacture large eVTOLs in 2022, which should accelerate aircraft development.

Furthermore, there are the service model issues. Regarding urban air mobility, Japan has a “Public-Private Council on the Air Mobility Revolution” that is studying use cases, but in Japan, with its well-developed urban transportation network, it is unlikely that services such as air-taxi will replace conventional transportation. Therefore, use case studies, including services, are being conducted using short-distance passenger transport for the 2025 Osaka Expo as a benchmark. Other use cases being considered include air mobility services in depopulated areas and resort areas rather than urban areas, but since the performance of the operating aircraft is not yet clear, a profitable service model has not yet been drawn. Initially, it is likely that the service will be provided by introducing aircraft from Europe and the U.S., where the airframe and operating models are more complete, and domestic development will follow these models.

Except for aerial photography, the drone industry in Japan has yet to become a profitable business, especially in the area of logistics, which is still in the stage of social experimentation with public subsidies. As for air mobility, only a few companies are developing air mobility through private funds or public funding, and it cannot be said that clusters for manufacturing have been formed. In addition, the authority for rule-making has not been transferred to the private sector, and the rules of Europe and the U.S., which are ahead of the competition, have not been successfully incorporated. In addition, there are very few academics interested in urban air mobility, including existing aviation. I think what we should learn especially from Europe is how to operate a sustainable and comprehensive urban air mobility team of private sector projects, and to collaborate with the competent authorities.

Unfortunately, Japan’s skills to manufacture aircraft from scratch have disappeared, and the industrial clusters that manufacture passenger aircraft and automotive components have the manufacturing quality, but not the capability to manufacture eVTOLs. Perhaps what Japan can contribute to the world is to support the global urban air mobility supply chain with high-quality manufacturing skills from small and medium-sized companies.

We feel that the scope of the AiRMOUR project is clear and the future of the service is easy to envision. It can be drone medicine transportation, blood transfusion and medicine express between hospitals, eVTOL dispatch of doctors and EMS service. They are emergency services and can be operated on an exclusive and priority basis, thus reducing physical risks such as collisions and increasing social acceptability compared to other air mobility services. As one of the standard protocols for medical care, we expect AiRMOUR to advocate various standards and operational criteria for air medical services. Japan has pioneered the service with private medical institutions and operators since the first air medical helicopter flew over the country 30 years ago, and a law on nationwide deployment was established 15 years ago. Japan is prone to natural disasters such as earthquakes and typhoons, and EMS with air mobility plays a major role. We look forward to AiRMOUR’s research on establishing air mobility services that complement helicopter functions.’

Professor Gaku Minorikawa is Special Advisor at JUIDA, Japan UAS Industrial Development Association. JUIDA is the only non-profit organization in Japan that seamlessly covers urban air mobility such as unmanned aerial vehicles and passenger eVTOLs. The organization is working to build a supply chain for urban air mobility. In the future, it hopes to develop into a comprehensive authority for the manufacture, operation, service, and management of air mobility, including eVTOL. JUIDA organizes the largest yearly Drone Exhibition and Conference in Japan: Japan Drone and International Advanced Air Mobility Expo. Furthermore, JUIDA publishes the Technical Journal of Advanced Mobility, an online journal dedicated to the exchange of information related to cutting-edge technology.

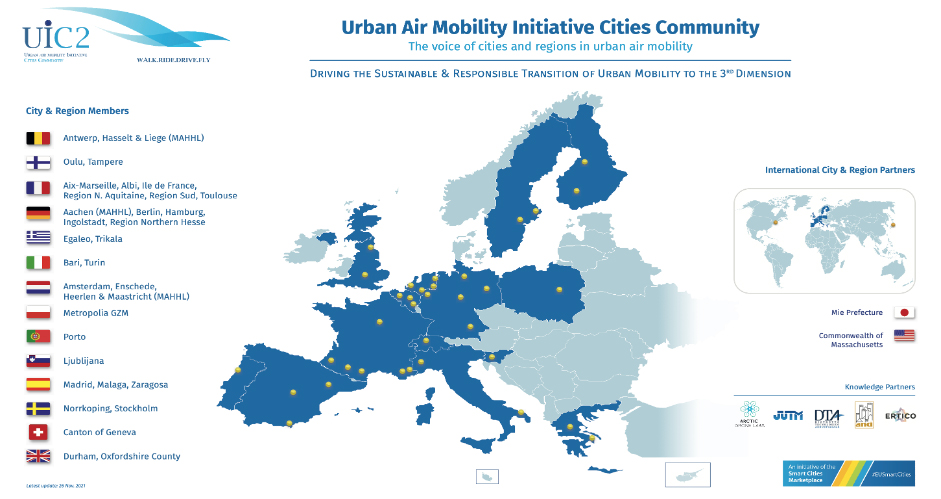

“I am very pleased to be in the AiRMOUR External Advisory Board in my role as Leader of the UAM Initiative Cities Community (UIC2) of the EU’s Smart Cities Marketplace. With the prospective increased use of Urban Air Mobility (UAM) worldwide, whether through drone services, or future deployment of so-called ‘air-taxis’ (eVTOLs) for passengers and cargo transportation, the low-level airspace above cities becomes subject to a new kind of airborne traffic.

To ensure a sustainable and responsible approach to the development of UAM services, it is important that cities and regions are informed and actively involved to ensure the integrated and sustainable planning for mobility, and wider urban development, for the benefits of their citizens. For example, critical time savings related to urgent medical deliveries and emergency services. Studies have shown that UAM medical services such as medical deliveries (e.g. blood deliveries by drone) and emergency services (e.g. eVTOL air ambulances) are most widely accepted by citizens and will therefore likely be the first permanent UAM services. The aforementioned prospects need focused research and cooperation between local authorities, the medical sector and the UAM (drone/eVTOLs) industry: that is exactly what the AiRMOUR project is doing through its 3-year duration (2021-2023).

The European Commission provides significant funding to bring Urban Air Mobility forward, from various different angles. AiRMOUR is one of the main projects focusing on medical services, public acceptance, safety aspects as well as the role of cities and tools to help them with this new form of mobility. The learning curve is steep and progress is fast, but challenges remain.

The UIC2 (UAM Initiative Cities Community) has an important role in shaping the future of airborne mobility above our cities and regions. The Amsterdam Drone Week is coming up in March 2022: topics related to urban air mobility in cities and regions are high on the agenda there, too. Let’s continue to build this important ecosystem together. Stay tuned for interesting outputs from AiRMOUR and hopefully see you in Amsterdam.”

Dr Vassilis Agouridas is Leader of the UAM Initiative Cities Community (UIC2) of the EU’s Smart Cities Marketplace, Head of EU Public Co-Creation & Ecosystem Outreach at Airbus Urban Mobility, and Chairman of the UAM Committee of ASD Europe.